Q&A: Ten for The TEN with Hanna Diamond

Historian reveals the double life of entertainer-turned-French Secret Services spy, Josephine Baker

Unique, comedic and utterly captivating. Josephine Baker was not just an entertainer, she was a tour de force.

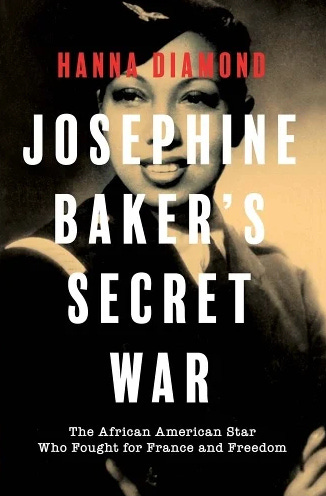

In Josephine Baker’s Secret War: The African American Star Who Fought for France and Freedom, a magnificently researched study from historian Hanna Diamond, we finally learn more about her time as a spy for the French Secret Services during the Second World War.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1906, Baker moved to France, where she transformed herself into an emblem of hope, resilience and liberation. Her journey from an impoverished childhood to becoming a celebrated performer in Paris is a testament to her unique voice, tenacity and unyielding spirit.

She broke the mould of conventional entertainment, and if you don’t know of her work, it’s worth taking a moment to look at the clips at the end of this interview, that demonstrate her singular skillsets.

With her iconic banana skirt and unabashed sensuality, she challenged racial stereotypes and redefined what it meant to be a black woman in the early 20th century. Baker’s strategic decision to perform in Europe rather than America not only advanced her career but also allowed her to escape the racial prejudices that plagued her at home. In doing so, she created a legacy that encouraged countless artists to embrace their individuality and unapologetically pursue their dreams.

Her life took a remarkable turn during World War II when she became a spy for the French Resistance. Utilising her fame and connections, she gathered intelligence that was vital to the war effort. She was not simply an entertainer; she was a courageous woman who used her platform to fight for freedom and equality.

This is one of the many stories from World War II that are only now coming to light. It’s important that we continue to shine a spotlight on those who fought for our freedoms, and so I was delighted that Hanna agreed to take time out of her busy schedule to answer my questions.

Hanna’s book, which is supported by a mountain of previously unseen material, explores this extraordinary period in the entertainer’s life, and is so far my read of the year. The storytelling is rich, visceral and so beautifully nuanced that I was immediately curious to learn more about how the author pieced Baker’s life together in such a compelling way.

Here, the author talks about the years of meticulous research that took her all over the world, why Baker’s celebrity gave her the perfect cover, and her enduring cultural importance.

Josephine Baker’s Secret War: The African American Star Who Fought for France and Freedom, by Hanna Diamond, is out now in hardback. Published by Yale University Press, it is available to order from their website, and all the usual outlets, including this one, and this one.

“The war period is key to understanding Josephine Baker. Her pre-war life experiences illuminate what motivated her commitment to the war effort and her willingness to risk danger” - Hanna Diamond

Hanna, thank you so much for talking to The TEN. You’re an author but also a professor of French History at Cardiff University, can you tell us a little about your career and areas of expertise?

I started teaching in Paris as a lectrice while I was completing my PhD there and really enjoyed it. Then I got a job as a lecturer at the University of Bath in the early 90s. It was in a department of European Studies (they no longer exist now sadly) and I enjoyed being the French historian for the department.

I thrived on all the connections I could make with other colleagues working in history, politics, international relations, cultural studies, film studies and gender studies in relation to their work on different European countries.

In 2014, I was appointed to a chair in the School of Modern Languages at Cardiff University. The large humanities offer there gave me further scope for collaboration, and I started working with a number of non-academic organisations in the cultural sector, including with media professionals and museums.

I became an advisor to the Musée de la Libération de Paris which relaunched its exhibitions in a new location in 2019, and in 2020, I co-curated its first temporary exhibition at the new site ‘Les Parisians dans l’exode’. I really enjoy working with a range of creatives and have further projects in the mix.

Throughout my career, I have built my research profile as a social and cultural historian of contemporary French history with a solid expertise in the Second World War publishing books and numerous academic articles on the topic.

My first ‘thesis’ book, Women and the Second World War in France: choices and constraints appeared with Longman in 1999, and my second monograph, Fleeing Hitler: France 1940, with Oxford University Press, dealt with the experiences of the millions of French people who fled during the German invasion. I have a strong interest in how individuals experience major historical events, and like to use personal narratives such as diaries and oral history accounts.

What is it about French history and WWII that captured your imagination?

I’ve always been a bit of a Francophile. I learnt to speak French quite fluently while still at school due to several French exchanges. Being able to communicate and make friends with those your own age is always such a bonus and enabled my language skills to go from strength to strength.

My interest in the Second World War came when I was a student during my Erasmus year abroad in Toulouse. There, I had my first encounter with archival research while writing my BA final year dissertation on their Jewish community. I developed a taste for research and working with archives, and started to read more about wartime France.

During my final year of my BA in History back at the University of Sussex, I was fortunate enough to follow a course on Vichy France with Professor Rod Kedward, a specialist of the French rural resistance. I was fascinated by the context of the Occupation and the ways in which it impacted on the French.

At that time, feminist and gender history were also forcing a reconsideration of the historical record to explore how women and men experienced history differently. With Kedward’s support, I was fortunate enough to attract funding for a PhD and set out to work on women’s experiences of the Second World War in France – how women coped often in the absence of the men, and the choices they made including the ways in which they were drawn into collaboration or resistance. From there, I was able to deepen and extend my knowledge with my ongoing research projects focusing on the period.

Your latest - and fifth - book, tells the story of Josephine Baker’s ‘Secret War’. Can you tell me how World War II become the missing piece in her story, and in what ways did her background as a performer - shaped by the racism she experienced growing up in the States - make her such an effective (and motivated) spy?

Yes, well, two of those five are edited essay collections, Josephine Baker’s Secret War is my third monograph or single-authored book.

I think, as was the case for many women who resisted in France, Josephine Baker’s wartime record was overlooked. The very invisibility that was so valuable to them at the time because it meant that they could operate in full view of the enemy while never falling under suspicion, played against them when it came to celebrating their achievements in the post war period.

In Baker’s case, as someone who had such public profile, I think her notoriety focused more on her more tangible and visible achievements. These include her extraordinary rise to fame from modest beginnings in St Louis, Missouri, her remarkable contributions to dance and music-hall in the Twenties and Thirties, her status as the first Black female film star before the war, and then her postwar involvement in the civil rights movement.

While Baker enjoyed some recognition for her war service, she was given a resistance medal in 1946, and the Legion d’honneur in 1961, she never spoke much publicly about her war record and when she did, she tended to brush it off as being a quite normal thing to have done.

In many ways, Baker’s success as spy feels quite counter-intuitive. She wasn’t at all the traditional kind of spy we might imagine who would melt into a crowd and pass unnoticed. To the contrary, Baker, an African American in France had instant recognition. She was often on the front pages of newspapers, in countless adverts endorsing products and on the many postcards in circulation which carried photographs of her, often posing with her cheetah, Chiquita. Baker adored animals and had a menagerie of them. Consequently, she tended to be besieged by crowds wherever she went, and she loved playing up to that role and carried it off brilliantly.

And yet, she was able to operate under the radar?

I think it was precisely because Baker was so successful as a performer, expert at projecting this image of herself that everyone believed in, that she was able to operate so effectively as an undercover operative. No one ever suspected that this, rather eccentric star, dressed in fabulous furs could possibly be a spy. She was therefore able to mobilise this very celebrity to support her activities collecting and transmitting intelligence for the French secret services, aiding the Allies and the Gaullist Free French resistance.

The advantages of her position supported her clandestine work in two important ways. Firstly, her fame gave her access to those in the know, to diplomats and dignitaries who, starstruck by her attentions, would reveal information to her, sometimes inadvertedly, never imaging that what they said to her would be repeated to those who would find it useful.

Secondly, she could move around when others could not. During the war, borders were closed, and it was virtually impossible to get the visas necessary to travel. However, if you were Josephine Baker planning to perform a series of concerts in Spain or Portugal, all the necessary visas materialised without question. This gave Baker a remarkable advantage. She had the freedom to travel which allowed her to observe situations, meet with people, collect information and pass it on to those who needed it when she returned home.

It was dangerous, but when Baker was invited to work for the secret services, she wanted to do her bit for the war effort and didn’t hesitate. She had taken French nationality when she married Jean Lion in 1937, and she wanted to pay back the people of her adopted country for their adoration, as a thank you for the fame she had acquired, which would have been impossible for her in her native country due to segregation.

Baker understood racism and celebrated the freedom she had experienced in France. She hated the Nazis, who had targeted her during her tours of Germany and Austria in 1929, and Lion, her husband was Jewish, so she was familiar with the threat posed by their antisemitism.

How did you bring together all the research you needed, and how long did it take to gather all materials before you started writing?

I started out with two key memoirs. Firstly, La guerre secrète de Joséphine Baker by Jacques Abtey who was Baker’s handler, published in 1948, and secondly, Joséphine by Joséphine Baker & Jo Bouillon published in 1976, just after her death.

My ambition was to uncover whatever sources I could to cross-check with these accounts as I suspected embellishment and inaccuracies. So, I set out on the archive trail which took me to numerous archive collections mainly across France and the US.

I was fortunate enough to have been awarded a two-year Leverhulme Research Fellowship which released me from my teaching and administrative duties at the University, so I could focus on the project.

While I did some writing and put together a book proposal, I spent much of that time doing research and collating it, as well as taking notes on secondary material. Baker spent time in multiple countries across North Africa and the Middle East, as well as in France, Spain and Portugal, so I had to do a lot of reading about the regions beyond Europe. This helped me to make sense of the archival material and understand its significance in relation to the complex wartime history of these areas.

You use previously ‘unseen material’. Can you tell me how you were able to locate this material and what you learned from it?

In short, I uncovered valuable material in several different quarters. At the French military archives, I accessed Baker’s military service files, as well as the records of all those who were linked to Baker at that time, including her handler, Captain Abtey, and her superior officer, Major Alla Dumesnil.

I also found several oral interviews. This archival material was supplemented with further information uncovered in de Gaulle’s archive collection at the French National Archives, and in the police archives.

These provided insights into Baker’s postwar anti-racist activity, and her correspondence with de Gaulle was quite extraordinary. In Nantes, I consulted Moroccan protectorate archives and the files of the French ambassador to New York, who reported on Baker’s visits there, and in particular on the events of 1951 when she came under attack for her war record.

In addition to these French archives, I worked on source material in the US National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and the Josephine Baker collection at the Beinecke Library, Yale University. At the National Press Archives, at the Library of Congress, the African American press during the period was very revealing. Various papers reported on Baker’s activities consistently and she loved to give the journalists interviews about what she was doing and why.

The Services and Entertain press also proved a useful source in relation to her performances during the period. Dossiers consulted in the UK National Archive relating to her work for the British wartime ENSA (Entertainment National Services Association) covered the work she did entertaining Allied soldiers in North Africa and the Middle East.

All these sources combined to bring new and detailed insights into Baker’s work not just for the Allies from September 1939 to November 1942, but they also reveal the significance of her ongoing clandestine and troop entertainment work for De Gaulle’s Free French Resistance movement. This included her activities in uniform as a second Lieutenant in women’s auxiliary of the French Air Force, until her decommissioning in September 1945.

When writing about a real person, especially an established figure such as Baker - who was in the public eye and known for her banana skirt and ‘savage’ dancing - what elements are you looking to pull together in terms of taking the reader on a journey that is factual, educational and entertaining?

My main priority was to create a readable and accessible account which did justice to the full extent of Baker’s war record and its significance – it really is quite a story!

I also wanted to reveal what this work meant to her both at the time and afterwards, and to show that she was more than a performer, bringing to light the multiple ways in which she mobilised her position to contribute to the war effort.

I was keen to draw on my extensive archival base to be clear about what we know happened, what may have happened and what probably isn’t very likely. There are so many stories told about her, many of which she promoted herself, and when it comes to spying, there are naturally some areas that we can never fully uncover because they were not recorded, and people did not speak about them at the time, or since.

I found Baker to be a very engaging personality and beyond the remarkable work she did as a spy, I was keen to put on record her other activities during the war.

Her commitment to troop entertainment, for example, was more than just a cover for her clandestine activities. She travelled extensively, often at risk to her own health, to deliver concerts in remote, sometimes dangerous, areas to perform on rudimentary makeshift stages.

Despite facing racism on the road, she had a deep enthusiasm for building soldier morale which has not been fully recognised to date. I wanted to convey this to my readers and to mobilise sources which allow us to hear her voice both through her press interviews and the memoir literature.

I also used the accounts of others who encountered her during the period, like British actor and comedy writer, Noel Coward, who met her in Egypt in 1943, as well the servicemen and entertainment journalists who attended her concert performances and commented on her vivaciousness and warmth.

What were the main challenges you faced when writing the book?

Finding the right balance between factual history and narrating her story. France’s role in the North Africa during the Second World War is very complex and in addition, Baker travelled around the Middle East where each country also had its own wartime context. I had to carefully weigh up how much history was necessary background for readers to grasp the importance of what she was doing and how she was doing it.

I hope I’ve equipped the reader with enough factual background to be able to appreciate the full extent of her contribution, as well as telling a good story without overly romanticising what happened.

The war period is key to understanding Josephine Baker. Her pre-war life experiences illuminate what motivated her commitment to the war effort and her willingness to risk danger, while her experiences during the war influenced how she lived her life afterwards in ways that have been underestimated until now. I hope I showed how assessing her life through the prism of her war service enhances our understanding of this astonishing and multifaceted woman.

How did you manage to write around your job because it’s an incredibly difficult balancing act. Did you have a regular schedule?

When it comes to writing, I do need to clear a spell of time as I tend to get pretty immersed. I’m best in the mornings, so I’ll sit at my computer soon after getting up with my first coffee and just write. I often carry on when I’m in the flow and don’t see the morning go by. I’ll push on until I need to stop for lunch and this can often be as late as 2 to 3pm.

After a break, if I don’t have to deal with other commitments and can carry on with writing, I’ll move over to a hard copy print out. I’m old school, and find that I need to combine screen work with hard copy for overwriting. I don’t see the text in the same way online and my eyes tire with the intensity of it. Sometimes, if I am struggling to express myself or need to plan a section carefully, I revert to pen and paper.

If I can’t ring-fence a full morning or an extended period for writing composition, I will use shorter spells to reread hard copy, correcting and overwriting or integrating handwritten corrections on the screen. I’ll also use such periods for seeking out secondary source materials and checking through my archive sources (mainly collated as photographs) to find missing information to fill gaps or overwrite sections that I’m not satisfied with.

“My main priority was to create a readable and accessible account which did justice to the full extent of Baker’s war record and its significance– it really is quite a story!” - Hanna Diamond

As a historian, you spend a lot of time doing research. I love working at the British Library but what is your most favoured, or treasured, library or archive, and why?

I do enjoy working in French archives but none of them come close to the wonderful National Archives, in Kew, which is a high bar to meet. It’s so lovely working there on every level.

Nonetheless, the National Archives, in Paris, once you have braved the journey there (it’s way out in the suburbs) and the frustration of managing the catalogue, all that toil evaporates once you get your hands on the material. I remember when I was there reading Baker’s correspondence with de Gaulle. I found it completely absorbing and was really swept away with it all.

And finally, what book are you writing next, or is it top secret?

I’m not completely sure but my work on WW2 in France, and my interest in women in the Resistance has made me think about the transition between the wartime and postwar experiences of women.

I’ve always been attracted by issues relating to women and power. French women only got the vote in April 1944, which seems so late, and there has never been a female president of France and rarely have there been women Prime Ministers. I’m interested in why that is, and I think we need to go back to the French Revolution to understand that.

So while I haven’t quite formulated how my next book will look, it may well focus on the lives of women in France in 19th to 20th centuries.

Follow Hanna on Instagram, Threads or Bluesky.

Josephine Baker’s Secret War: The African American Star Who Fought for France and Freedom, by Hanna Diamond, is out now in hardback, and on Kindle. Published by Yale University Press, it is available to order from their website, and all the usual outlets, including this one and this one.

If you’re eager to learn more about Josephine Baker (after reading Hanna’s book of course), she has a few recommendations. “There are some amazing clips of her extraordinary dancing online which give us insight into her frenetic dancing style and help us to understand the shocking impact she must have had on audiences at the time she arrived in France in the 1920s.”

And this clip is just delightful. Josephine appears at around 10.50. As Hanna says: “It’s remarkable how she reaches out to her spectators, and many servicemen wrote about how they felt like she was singing just for them!”

Hanna was also involved in the Channel 4 documentary, WW2, Women on the Frontline. Episode One tells Josephine’s story.

She also recommends the 2005 BBC documentary Josephine Baker: The First Black Superstar, which is currently available on iPlayer. I watched it as I was editing this interview and it contains remarkable footage of Baker through all of her colourful eras.

Josephine Baker at her home, the Chateau Les Milandes, in the Dordogne, in 1961. She died 14 years later, aged 68.

I always love hearing about this. It's just so wild! And what a great idea, bc who would Ever suspect a gorgeous entertainer of being a spy.