Q&A: Ten for The TEN with Penny Haw

South African novelist champions trail-blazing women of history

One of my favourite movies is Hidden Figures, which tells the true story of Katherine Johnson, a brilliant mathematician who overcomes institutional racism to work in NASA’s Space Task Group, as their first black female engineer.

Portrayed brilliantly by Taraji P. Henson, I'm a sucker for stories that show strong women, who excel in their field.

Another is Hedy Lamarr, the Hollywood actress, who during WWII, invented a frequency-hopping system that become the foundation for the WiFi and Bluetooth communication we use today. Gal Gadot is set to play Hedy in a new Apple + series, which underlines once more that brilliant women are (rightly so) all the rage.

And that’s why the heroine of author Penny Haw’s latest novel sits right in my sweet spot.

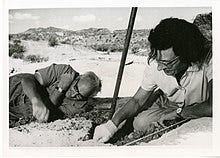

Follow Me to Africa, is inspired by the life of distinguished paleoanthropologist, Mary Leakey, who played a crucial role in understanding human evolution through her work. Significantly, she discovered the first fossilised Proconsul skull, an extinct ape which is now believed to be ancestral to humans, and in 1978, she unearthed a 3.5 million-year-old fossilised footprint, which provided strong evidence that early humans walked upright.

Her story is tailor-made for historical fiction, which is why former journalist Penny, who lives in South Africa, and who has made it her mission to bring women such as London-born Mary to life, found it so enticing.

Follow Me to Africa is now available to pre-order and will be published on March 25.

Penny’s previous works of historical fiction include The Invincible Miss Cust, based on the life of Aleen Isabel Cust, who defied her family, and society, to become Britain and Ireland's first woman veterinary surgeon, and The Woman At The Wheel, about Bertha Benz, whose husband built the first prototype automobile.

So, without further ado, and before we all start to fossilise, here’s what Penny had to say about her desire to showcase pioneering women of history, her writing process that includes self-imposed deadlines, and why living in South Africa inspires her creativity…

“The joy of writing historical fiction is being inspired by the facts and filling in the gaps with speculative delight, with the ultimate objective of entertaining readers” - Penny Haw

Thank you for talking to The TEN today, Penny. Can you tell us about your career and where you live?

I was raised on a farm in the soft-hilled, southeastern KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. After I graduated from university, I moved to Cape Town in the Western Cape, where I’ve been ever since.

I worked as a journalist until I began writing fiction about eight years ago. My home, which I share with my husband and three excitable dogs, is in the fishing village of Hout Bay, little over 20 kilometres from Cape Town.

It’s a beautiful spot where the icy Atlantic Ocean crashes against the mountains, except where it’s tamed by sandy, white beaches.

What inspired you to become a novelist?

I’ve told stories for as long as I remember. As a child, I spent hours roaming the farm, regaling my dogs with lengthy fictional stories, radio-play style. When I began reading, I was hooked and dreamed of being an author. At boarding school, I wrote and (badly)illustrated a series of stories about a family of ants. Episodes were circulated among my friends while we allegedly did our homework in the evenings. I had an audience. My first readers!

However, fiction was placed on the back-burner for decades while I worked as a journalist. It was only in 2017, when I wrote my first book - a children’s story called Nicko - that I returned to it.

Nowadays, I’m lucky to write fiction full- time. I love the playfulness of it. It’s as if I’ve come full circle. If I wasn’t clicking away at my keyboard, I could be traversing the hills, performing my tales to my dogs once more.

Your third work of historical fiction, Follow Me to Africa, is informed by the life of distinguished paleoanthropologist, Mary Leakey. Why were you drawn to her?

Mary Leakey, and her husband Louis, led research into humanity’s origins, in Africa, at a time when European scientists were certain that Europe - or, okay, maybe Asia - were the cradles of mankind.

I came across the Leakey’s work years ago, but it was only when I read Mary’s autobiography, Disclosing the Past, that I realised just what a remarkable woman she was. I immediately related to her love of Africa, the outdoors and animals, and to how she enjoyed being alone in the wild. I admired her independent spirit and curiosity, and her dedication to her work.

When I discovered she hadn’t received a typical education and was largely self-taught, I was utterly intrigued. I’m excited by stories of people who pinpoint what they’re curious and passionate about and pursue their dreams against the odds.

In addition, I was inspired by the way Mary quietly but determinedly extricated herself from Louis Leakey’s shadow.

How do you begin the task of researching somebody’s life, and then decide what to keep in terms of fact and also, what to fictionalise?

My methods of research for historical fiction are like those I use for journalism: I read and watch relevant material to learn as much as possible; interview experts on the character and her field; and visit and explore places and settings.

Because she was a scientist, Mary wrote a great deal, including an autobiography. As such, I decided not to write her story using a singular, first-person point-of-view like I did for my historical fiction about Aleen Cust, in The Invincible Miss Cust, and Bertha Benz, in The Woman at the Wheel. Mary’s voice is already established in literature, and I didn’t want to try to emulate it.

In Follow Me to Africa, I make use of two timelines - the 1930s and onwards for Mary’s story, and 1983, for that of Grace Clark, an entirely fictitious young girl who meets Mary on site in Tanzania.

I wrote the story from both women’s perspectives because, in addition to telling Mary’s story, I wanted to impart something of what she’d might’ve learned to someone younger. I liked the idea of Mary looking back and imagining how she would counsel her 17-year-old self. Grace is the foil for this.

Of course, I’ve imagined conversations, thoughts, emotions and some relationships. The joy of writing historical fiction is being inspired by the facts and filling in the gaps with speculative delight, with the ultimate objective of entertaining readers.

What is your typical writing routine?

I have a boringly business approach to writing and work traditional work hours. Having worked as a journalist for so long, I’m motivated by deadlines and, where they’re not imposed by others, I set them for myself. I don’t look for the muse, wait for motivation, or hope for creativity to magically appear; I go to my computer and get to work. It helps that writing is a pleasure for me. I get such enjoyment from it that I’m happy to be at my desk all day.

A dream workday follows a walk on the mountain with my husband and dogs and an uninterrupted day at my computer. At 5 pm, I hear the familiar clatter the dogs scampering upstairs to remind me it’s suppertime. After I’ve fed them, I settle down to write for another hour or two.

What is your revision and editing process like, and how closely do you work with your editors?

I work closely with both my agent and editors. My agent, Jill Marsal is a founding partner of Marsal Lyon Literary Agency and has a wealth of knowledge and experience. I rely on her to advise and guide me on the book business and am grateful to have her in my corner.

Likewise, I’ve benefitted a great deal from the expertise, knowledge and feedback from my editors at Sourcebooks Landmark. It’s been a joy to work with Erin McClary and Liv Turner. I’ve found every book different in terms of how much work is required during revisions and editing but enjoy the collaborative process of working with others to improve a manuscript. It’s such a privilege.

I can see your novel, The Invincible Miss Cust as a TV series. Why do you think in this digitally driven world writers, and audiences, are so keen to explore the past?

I’d love to see my books translated to the screen. Yes, there does seem to be a resurgence of interest in history among writers and audiences. We’re fascinated by the past because it both helps us understand current times and escape them!

I love writing and reading historical fiction because it’s a fun way of turning back the clock and stepping into the shoes of people who lives were different from ours and yet, whose dreams and hopes were the same. It’s also a way of exploring the more personal, emotional side of history.

Historical fiction brings history alive by allowing us look at people’s motives, choices and inner worlds. I believe it brings new audiences to history. People who don’t necessarily read history in non-fiction form are drawn to the stories and characters they’re introduced to in fiction. When they’re done well, historical fiction and movies/series are immersive, bringing interesting characters to life.

As American novelist, E L Doctorow is said to have said, “The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.” I say, facts inform, feelings stir.

Your first book, Nicko: The Tale of a Vervet Monkey On An African Farm, was published in 2017. Why a children’s book and will you write another?

I think of Nicko as my ‘gateway book’. It’s the story of my grandmother and an orphaned baby monkey. Although I always wanted to write fiction, I was uncertain, terrified even about doing so, after working as a journalist for many years.

Nicko was the story my grandmother told me. There was something certain about it and I decided to test myself by retelling it for children. It’s possible I’ll write another children’s book but I don’t have immediate plans to do so.

You use the backdrop of Africa to great effect. It clearly inspires you but what influence does it have on your writing?

Much of my childhood was spent outdoors. I know and love the bush and its wildlife and have always spent as much time as I can in the wilderness. I’m soothed and inspired by the outdoors and animals (both wild and domesticated).

Fauna and flora are so integral to my enjoyment of life that writing about them seems unavoidable and natural to me. Nature inspires me. Mary Leakey loved Africa. She was happy being alone on the edge of the Serengeti among the animals. It gave me pleasure to imagine and write about her enjoyment of Africa.

I love that Follow Me to Africa has a glossary; Clactonian, Oldowan and Pleistocene are all new to me. Do you have fun compiling them and what are your favourites?

I’m a great fan of glossaries and included one in The Woman at the Wheel and the novel that follows Follow Me to Africa. I made notes as I researched and wrote, and I particularly like the ones that come from African languages, like ‘boma’ and ‘korongo’.

If we were to get a POV of your desk, what would we see?

Oh! This is fun. I have a small fan rattling as it blasts cool air at me. It’s summer in South Africa! There’s a large, blue mug with polka dots on it, which contained rooibos tea infused with mint.

A messy queue of Post-it notes curls up along the bottom of my computer screen. Inscribed upon them in my haphazard left-hand scrawl are reminders of the primary points of my developmental edits of my work in progress. They’re nonsensical to anyone but me. “Which is the moon, and which is the planet?”, “Why give up music?”, “Loves stars. When? Why?” and “The scars. The stunting.”

You’d also see a row of different coloured pens, a miscellany of charger cables coiled like sleeping snakes, and a tube of hand cream. The latter has been there for years, unused, because I dislike its sickly-sweet fragrance. I’ll discard it immediately!

And finally, can you tell us about your next book?

My fourth work of historical fiction with Sourcebooks Landmark will be published in 2026. It tells a story of Caroline Herschel, who, in 1787, became the world’s first paid woman astronomer. Caroline was born and raised in Hanover, where, scarred by smallpox and stunted by typhus, she was destined for a life of servitude at the bidding of her mother and oldest brother.

Everything changed when another brother whisked her off to England, where he was working in Bath as a musician and amateur astronomer. Thus began Caroline’s interest in stargazing, which opened unexpected doors.